Chapter 21: Twilight of the Regime: 1969-1973

"The ceremony of July 1969 finally solved the immediate question “After Franco, who?” It did not necessarily answer the accompanying query “After Franco, what?”"

MATESA Affair

"Even though the new development program was geared for increasing exports, financial regulations still did not readily assist sales of machinery abroad but had been designed to encourage finished consumer goods. Vilá Reyes was unable to obtain export credits without being able to present firm orders for his products; since these were slow to develop, he inflated orders through his own subsidiary firms to gain credits from the governments Banco de Crédito Industrial. Vilá later insisted that officials were adequately in- formed beforehand of his modus operandi, required by the rigidity of the Spanish financial structure. The credits involved were quite substantial and the irregularities eventually became more widely known. They were formally denounced on July 17, 1969, by Victor Castro San Martin, an old-guard Falangist and director general of Spanish customs. The charges were debated by the cabinet in August. There was no doubt that Vilá had been involved in irregular procedures, but considerable uncertainty existed as to the extent of complicity in higher circles of government. The issue was quickly seized by Movement leaders to discredit the Opus Dei economics ministers, who were at a loss to quiet the affair, even though irregularities in official financial dealings had been a way of life in much of big business since the start of the regime.

The scandal was made public in mid— August and was investigated by a Cortes commission the following month. The press was given broad freedom to report the case, and indeed, the Movement organs led the charge in denouncing fraud,' hoping thereby to discredit the economics ministers who had gained the upper hand in the cabinet during the past decade and secured the recognition of Juan Carlos. Vilá Reyes had enjoyed good relations with government personnel who were members of Opus Dei, and it was loudly whispered that some of the funds unaccounted for had been sent abroad to finance the activities of Opus Dei in other countries. The facts in the affair were so complicated that they have still not been fully clarified after nearly two decades. The defense claimed that MATESA’s basic operations were in order until widespread negative publicity provoked massive cancellation of orders, and that all losses on orders supported by government credit had been fully insured, though the government made no effort to require the insurance company to pay. A subsequent investigative report released only in 1981 concluded that the firm had total assets of more than 14,000 million pesetas and despite outstanding debtsad retained a positive balance of approximately 1,000 million pesetas.? Whatever the full facts, Vilá Reyes was arrested and his corporation taken under government control.

For Carrero Blanco and López Rodó the scandal was an acute embarrassment, coming on the very heels of their signal victory in wringing the recognition of Juan Carlos from Franco. The Caudillo, however, had made his choice, and had come to rely much too heavily on his vice-president and the latter's closest associates to permit the triumph of the Regentialists who had been combating them for the past seven years. As repercussions mounted, it became clear that the ministers of finance and commerce, Juan José Espinosa San Martín and Fuastino García Moncó, allegedly implicated in varying degrees, would have to go, but this would be balanced by the elimination of the principal Regentialist and Movement figures, producing a broad cabinet reorganization. To Carrero, Fraga Iribarne was a “dangerous liberal” who had opened Spain to Marxism and pornography, while the minister-secretary of the Movement, Solís, was painted as a dangerous intriguer, a veritable new Salvador Merino of the Syndical Organization who sought to establish the dominance of the labor bureaucracy within the system. To a lesser degree Castiella was also a target, blamed for the abrupt, graceless, and destructive decolonization of Guinea and for conniving with liberal currents in the Vatican."

"By this time it was Carrero Blanco much more than Juan Carlos who had come to represent the succession to and continuation of the regime. Franco obviously saw him as his natural successor as president of government, the surviving prime minister who would guarantee that the transition to Juan Carlos would take place under strict continuation of the laws and institutions of the regime. Carrero Blanco's success was due in large part to his strict personal fidelity to Franco and his lack of overweening ambition for himself. He was an introverted and retiring man of absolutely fixed and unremitting ideas, totally convinced that the world in general was dominated by the “three internationals,” as he termed them, of Communism, Socialism, and Masonry. The father of five children and grandfather of fifteen, he spent a very large part of his time reading and writing,° and continued to prepare sizable memos for the Caudillo, though not at such great length as in the past. He was largely immobilist with respect to major domestic institutions, and viewed foreign affairs in similarly intransigent and apocalyptic terms, holding that it would be preferable for all his descendants to die in an atomic war than survive as slaves of the Soviet Union. "

"Meanwhile the MATESA affair ground slowly on. In the following year the Spanish Supreme Court indicted both of the outgoing ministers who were implicated, as well as the former finance minister Navarro Rubio® and six others. Vilá Reyes was himself convicted of wrongdoing and sentenced to a large fine and several years incarceration. While in prison awaiting an appeal, on May 5, 1971, he directed a blunt letter to Carrero Blanco, warning that if the government did not take action to absolve him in some fashion he would make public extensive documentation that was in his possession concerning widespread smuggling of funds abroad during the years 1964—69. His letter included a “documentary appendix listing various materials that he could present dealing with such activities by 453 leading individuals and business firms, many of whom were closely connected with the regime.* This well-documented threat seems to have achieved results. Carrero convinced Franco that if the whole business were not soon hushed up it would reflect even greater discredit on the government and might even do irreparable damage to the regime. Sevral months later, on October 1, 1971, the thirty-fifth anniversary of his elevation to the Jefatura del Estado, Franco granted an official state par- don to all the principals involved, feebly camouflaging it by a general par- don to more than 3,000 others still suffering the penalties of political convictions in earlier years. There had as yet been no trial save for the preliminary prosecution of Vilá Reyes and hence no verdict save in that one case, though the financial inquiries involved would extend for more than a decade further, beyond the end of the regime and well into the 1980s. Attended by major publicity under the relaxed censorship and oc- curring at a time of growing mobilization of political opinion, the whole scandal probably brought more discredit on the regime than any other single incident in its long history."

The Movement in Paralysis

"After initial approval of the Statute on Associations on July 3, 1969, four distinct groups had begun to take the initiative in forming associations...As of late 1969, however, all this was beside the point, since Franco had never ratified the Statute on Associations. Neither Franco nor Carrero Blanco approved of the idea of associations, yet they did not take the step of quashing the idea altogether, probably for lack of any other reformist alternative. "

"Fernandez Miranda held that the “pluralism” of political parties could never be accepted but that the “pluriformism” within unity of the Movement could still provide opportunity for participation in some form of associationism.'...Thus the Movement leadership continued to manipulate the standard rhetoric, augmented by occasional new terms but no new concepts.”"

"Yet an aperturista minority did exist within the Movement and the Cortes, and at the beginning of 1970 a small group of reformist members of the National Council, led by the former vicesecretary general Herrero Tejedor, presented a petition to Fernandez Miranda, urging that arrangements for political associations be speedily brought into effect. "

"Fernández Miranda kept his word not to forget the associations project and on May 21 presented a new draft outline for associations of political action to the permanent commission of the National Council. This stipulated that any proposed political association must consist of no less than 10,000 signed members. "

"There the project remained for the next three years. Franco and Carrero Blanco quickly drew back before even such a carefully controlled scheme, and the associations project was buried, further discussion by the National Council avoided. On February 15, 1971, the family representatives in the Cortes attempted to interpellate the government on this issue but gained no satisfaction. When the National Council finally met again two days later, political associations were not on its agenda. One fur- ther effort was made by reformists to air the issue in the press and other forums in the spring of 1972, but by that time Fernández Miranda had received clear orders. Echoing the terminology of Franco, he declared publicly that any action which attempted to reintroduce political parties would be a mere “dialectical trick,” and in November 1972 informed the Cortes: “To say yes or no to associations is simply a Sadducean trap. . . . The question is to see whether in saying yes to political associations we also say yes or no, or whether we do not say yes or no, to political parties.” **"

"The Falangist old guard, largely displaced from the direction of the Movement itself since 1957, persisted in their traditional rhetoric, holding that only in reviving the Falangism of the regime and restoring a Falangist program would survival and continuity be assured. "

"The “alphabet soup” of tiny neo-Falangist dissident group- lets continued, with a half dozen new ones formed during the first half of the 1970s.” "

"Neo-Falangism surpassed even the revolutionary left in its divisivenessand internal schisms. This of course reflected the normal sectarian fac- tionalism and exclusiveness of the twentieth-century radical political religions of whatever stripe, but in the Spanish case also seemed to express an unusually high degree of anarchic personalism and voluntarism, qualities most salient in the neofascist culture. This divisiveness might have been partially overcome if any one of the grouplets had generated any support.” None did, however, and post— Franco elections would show that all the neofascist elements combined could not muster two percent of the popular vote, though of course José Antonio's original movement had doneeven more poorly in 1936.

Not only had Falangism reached a state of terminal confusion, but the other original primary constituent of the Movement, Carlism, was in pro- cess of a kind of reversal of ideologies. Under the uncertain leadership of “Carlos” Hugo, the main group of neo-Carlists came out for el socialismo autogestionario (self-managing socialism), the leading new catchphrase of the Spanish left by the early 1970s, derived from French Socialist terminology.” Even before the death of Franco, the primary forces of the origi-nal Movement had become totally eroded and ceased to exist as viable political options.”"

Last Phase of the Syndical Organization

"Since the mid-sixties Solis Ruiz had been preparing a major new reformist syndical law which was finally presented to the Cortes on October 3, 1969. Its basic intent was to endow the Syndical Organization with autonomy and to make it a much more representative institution, with lower- level leaders to be elected by the membership "

"Solíss successor, García Ramal, pursued some of the same policies with more political prudence. There was continued emphasis on making aspects of the Syndical Organization more representative, expanding benefits for workers, and codifying new reforms in a syndical law that would replace Solíss abortive project. "

"In the wake of the new syndicates law an extensive series of reforms were carried out. Workers” rights of assembly were broadened, lower-level syndical officials received more autonomy as well as a partial guarantee of greater security in their positions, workers” rights of legal appeal were extended, and a new welfare jurisdiction (Tribunales de Amparo) was created. Social assistance was increased, a number of professional colleges were formed, and in general, both the range of activities and the opportunity for worker participation were increased.* On July 1, 1970, an elderly Caudillo even admitted, to the applause of many thousands of workers dutifully assembled in Barcelona Ciudadela Park, that some of the poorer in the nation were still not sharing equally in the benefits of the great economic boom.” When the next national syndical congress was held in 1973, nearly all the delegates and officers were elected by the workers. Nonetheless, the president of the Syndical Organization continued to be named by the chief of state, and the basic chain of command remained vertical. Though workers had greater autonomy, rights of participation, and economic justice, the system was still one whose frame- work was organized and ultimately controlled by the state. Though major public relations efforts had been made during the past decade, even including extensive questionnaires about reforms distributed among workers, the basic right to strike or form independent unions was never even mentioned. Thus all the nominal changes, though they did introduce a semipluralism and a limited freedom of expression, had no effect whatsoever in pacifying industrial labor."

"The strategy of the Syndical Organization was to combine somewhat greater freedom with firm repression of those active in labor disputes...and for the first time strike actions were undertaken by professionals such as doctors and teachers and white-collar workers such as postoffice and bank employees. "

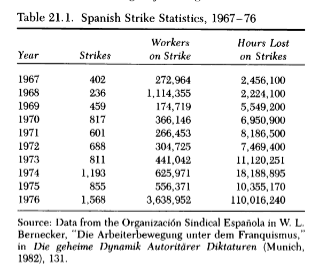

"By the early 1970s there were several cases of strike actions virtually expanding into area general strikes, particularly in the Basque provinces of Vizcaya and Guipúzcoa, where collective actions were more directly politically motivated than in any other part of Spain. It is true that during the entire history of the regime no sector of the economy was ever crippled or paralyzed by strike action, and such key areas as transportation, tourism, and electricity were scarcely ever affected"

The Growth of Opposition

"Opposition continued to function at three different levels. There was a sort of loyal opposition consisting of semi- liberals and reformists within the system and the Movement itself, who wished to reform rather than overthrow the regime. There continued to exist a semilegal opposition of middle- and upper-class monarchists and Christian democrats, whose activities were never directly legalized but frequently tolerated, and beyond it lay the illegal opposition of radical and revolutionary groups that was still directly (though never totally) repressed. The radical opposition in turn was made up of three primary elements: university students, industrial labor, and regionalists.*!

On December 23, 1969, 131 of the principal leaders and intellectuals associated with the semilegal and illegal opposition presented an open letter bearing their signatures to Franco. It rejected the concept of restricted political associations within the Movement and demanded democratic reforms. Though the Caudillo was unimpressed and made no response, neither were there serious reprisals.

Throughout the later years of the regime, the great bulk of even the leftist opposition was moderate and restrained, for it had little hope of fundamental change until after the death of Franco. This was as true of the well-organized Communist Party, largest and most active of the hard-core opposition, as it was of the Socialists and most smaller leftist groups."

"Violent opposition was restricted primarily to a new revolutionary form of Basque nationalist resistance (ETA), and to a much lesser degree, a subsequent minor Marxist terrorist organization in Madrid (FRAP). Radicalization of some of the youth in the Basque nationalist movement is explained in considerable measure by the vertiginous social and cultural changes that tock place in the Basque country during the 1960s. Secularization struck a still largely religious society with great impact, while the most intensive pattern of urbanization and industrialization in the entire peninsula engulfed a society of villages and small towns. Between 1950 and 1970 the population of the Basque provinces swelled more than 60 percent, from approximately 1,500,000 to more than 2,400,000, most of it resulting from massive inmigration of non-Basque workers. Formerly semirural areas were transformed into almost solidly industrial zones, destroying ancient patterns of landholding and traditional ways of life and producing extraordinary cultural disorientation and anxiety, the blame for which was often projected outward onto the encompassing Spanish environment. Destabilization of a tightly integrated religious and distinctive regional culture in Vizcaya and Guipúzcoa thus had quite different consequences from the migration of peasants from Andalusian or Leonese villages. Those displaced peasants simply moved away, often never to re- turn, but hundreds of young Basques responded to the trauma of drastic change and continued centralized repression by developing a violent resistance organization of students, young workers, and young middle-class employees. The new movement, ETA, raised the most direct challenge to the regime that it was to face in its last years.”"

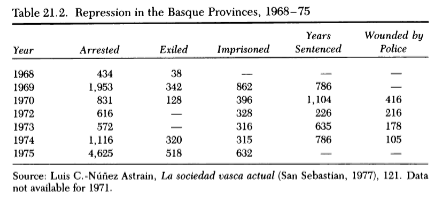

"The first fatality exacted by ETA gunmen occurred in 1968 when the head of the Brigada social (political section) of the police in Guipúzcoa was shot at the door of his home partly in retaliation for the earlier killings of two etarras. Several ETA leaders were captured in the resulting crack- down (which produced nearly 2,000 arrests in the Basque provinces dur- ing 1969), and military prosecutors eventually decided to place those most responsible for violence on public trial. The reason for this unusual show procedure was the calculation that public exposure of the violent methods and revolutionary aims of ETA, who by late 1970 had killed three members of the security forces, would build public support for the regime against its challengers. This calculation, opposed by some in the government, proved to be a major mistake, for the publicity generated by the resulting court-martial had the opposite effect. ETA had been consider- ably weakened by the repression of 1968-69, and according to some re- ports was threatened with internal breakdown. A plan to assassinate Franco near his summer residence in Galicia in 1970, possibly the major nonanarchist assassination plot in the history of the regime, had to be aban- doned for lack of organizational infrastructure.* The court-martial of the leading ETA prisoners at Burgos in December, however, resulted in a flood of favorable publicity that helped to revive and expand the movement.

All the leftist groups gave the trial as much attention as they could, stressing that court-martial procedures merely exemplified the military and repressive nature of the system. On August 18, an old gudari (Basque Nationalist soldier of the Civil War) set himself afire and threw himselffrom the upper level of a frontón in San Sebastian in front of Franco, at- tending a jai-alai game there. The pope publicly requested leniency for the accused etarras while the leadership of the European Community urged “maximum clemency.” On December 2 ETA activists kidnapped the German consul in San Sebastián, after which guarantees were sus- pended in Guipúzcoa for three months, and then more briefly for all of Spain."

"The consequence of all this, nonetheless, was to refurbish the image of ETA among Basques generally and young Basques particularly and to re- emphasize the general image of the repressiveness of the regime."

"The youth of the accused, their burning enthusiasm and dedication to the Basque cause, the severity of the initial sentences, the obvious sympathy of a large portion of the Basque clergy for the accused (two priests were among the indicted), and the general outpouring of international sympa-thy and appeals on their behalf—all had a profound effect on Basque opinion. The government was completely unable to find any formula that might have conciliated some of the moderates in Basque society, other than minor concessions for part-time ikastolas (Basque language schools). Repression was simply increased, though not to the level that would have been necessary to stamp out dissidence "

The Ecclesiastical Revolt

"A potentially even more serious source of dissidence than radical Basque nationalism was the drastic change in the policy of the Church, coupled with the active political dissent of much of the younger clergy. The liberalizing reforms and redefinitions of the Catholic Church’s Council of Vatican II, which were concluded in 1965, had probably a greater impact in Spain than in any other country, if only because Spain had hitherto been more conservative than any other major Catholic country."

"From petitions in the early 1960s they had moved to protest marches in Barcelona in 1966 and then to occupations of buildings and to independent politicized assemblies, all of this accompanied in the larger cities by inflammatory sermons and agitation by individual priests. A few of the most radical proclaimed the need to put an end to capitalism and solemnly declared that “exploiters” could not expect to receive the sacraments in a state of grace. Christian-Marxist dialogues, either clandestine or conducted outside of Spain, became all the rage. Hundreds of clergy were involved in political activities that a quarter- century earlier would have brought immediate imprisonment, beatings, and long prison terms to laymen. Since the clergy had special juridical privileges under the Concordat, they were treated with kid gloves, how- ever. "

"All this provoked a new kind of anticlericalism never before seen in Spain, the anticlericalism of the extreme right. Publications of old-line Falangists and other ultrarightist groups were given relative license in their verbal attacks on the “red clergy,’ and there were occasional physical assaults as well. In July 1971 the minister of justice publicly protested the “Marxistization” of the Church, echoing the language of a report presented by the minister of the interior six months earlier on the penetration achieved by subversive groups and ideas."

"Abandonment of the traditional Spanish ideology by the greater part of the clergy filled Franco and Carrero Blanco, its last major historical avatars, with perplexity and a certain consternation. At a meeting late in 1972 with the liberal Cardinal Tarancón, new president of the Episcopal Conference, Carrero Blanco reiterated the devotion of the Spanish state to the Church, pledging that it was prepared to do even more juridically and financially and that all it asked in return was that the Church be its firmest support...It was conceptually extremely difficult for the leaders of the Spanish regime in their old age to grasp that the Church no longer thought in such traditional terms, and the very last years of their lives were to this extent a time of bewilderment."

Educational Reform and Expansion

"Shortly before his death, Franco complained that the trouble with most of his education ministers was that they had been professors more interested in protecting their own guild interests than in developing sound education."

"For the first time in Spanish history, national elementary education became compulsory, since for the first time the state possessed resources to begin construction of schools adequate for the entire population. A new program of educación básica general was instituted for the first eight years of schooling, divided into two different cycles. Secondary education was reorganized around a three-year cycle (in the Institutos Nacionales de Ensenanza Media), plus a pre-university year for those going farther. The university system was geared to three cycles: a three-year undergraduate cycle, a two-year professional degree sequence, and the doctorate. In addition, plans were laid for expansion of vocational and adult/extension programs.”

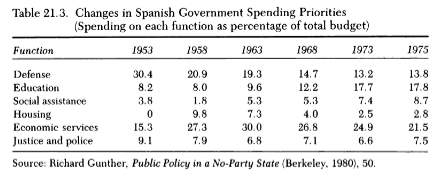

As late as 1964 Spain had been spending only about 2 percent of its GNP on education (not counting private and religious schools, which were numerous), less than any other European country save Portugal. Several World Bank Loans were obtained to expedite reform and expansion, so that between 1969 and 1971 spending on education increased 66 percent in constant pesetas. "

"This was proportionally the broadest educational reform and expansion being attempted anywhere in the western world. It challenged the vested interests of veteran teachers and professors and of some students who had partially completed the requirements of the old system. At the universities it roused strong protests from both radical students and reactionary professors. In more objective terms, the reform tried to do too much too fast and was often poorly administered, with Diez Hochleitner resigning under considerable fire in mid-1972. The university student population, about 150,000 in 1969, increased to nearly 400,000 by the time of Franco’s death six years later. This academic population explosion produced a volatile mass of new students for whom adequate facilities were often lacking, and only reinforced the tendency among universitarios toward disaffection and strong political opposition. There is little doubt that the educational reform and expansion, one of the prouder achievements of the regime's later years, contributed significantly to its partial destabilization. "

The Military During the Final Phase

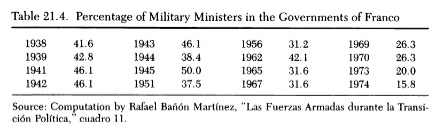

"Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, whenever worried supporters pressed Franco about the question of the succession and the future, he usually responded that no one need worry, for in extremis there was always the Army, which could be relied upon to defend the institutions of the regime and guarantee continuity. This assurance was well founded to the extent that the Spanish military remained fully identified as Francos own Army to the very end. The officer corps, with only the fewest exceptions, supported the regime and always looked to Franco as their Caudillo. Yet he had managed to develop an institutionalized system rather than a merelpretorian or military regime, and had always been successful in avoiding political intervention by the military while retaining their political loyalty. Though many senior officers had participated in government, they did so not primarily as representatives of the armed forces but as individual administrators in formal state institutions which recruited on a semi- pluralistic basis. Moreover, the number of military personnel in cabinet positions declined noticeably after 1951, dropping from nearly 50 percent in some of the first governments to 32 percent in 1965 and to 26 percent in 1969. In Francos final government of 1974-75 only the armed forces ministers themselves were of military background.* To a certain degree Franco encouraged professionalization and the attitude that the function of the military was to serve rather than to dominate. Thus he not only trained the officer corps to serve his own regime faithfully but he also, however ironically, began its preparation to adjust to an apolitical role during the democratization of Spanish institutions after his death."

"resentment increased among ultra officers in the face of the governments subsequent vacillations and commutation of sentences, leading to semisecret meet- ings in a number of garrisons during the closing days of 1970 that were said to have involved hundreds of officers. A subsequent decree of Novem- ber 1971 finally reduced once more the jurisdiction of military courts, so that, according to the Anuario Estadistico Militar, the number of civilians sentenced by such tribunals dropped from 403 in 1970 to 231 in 1971 and 222 in 1972.

Franco was fully aware that one of the main deficiencies of the modern Spanish army lay in the hypertrophy of its officer corps and the excessive share, sometimes up to 80 percent, of the budget devoted to salaries, leaving much too little for equipment and training."

"Much of the manpower was provided by an annual contingent of be- tween 100,000 and 150,000 draftees, who served for eighteen months, while volunteers enlisted for two years. One of the most necessary re- forms, however, was to lower the retirement age, much higher than in most other armies, so as to remove the elderly, superannuated, usually not fully competent generals who made up the swollen senior echelon, yet this was never seriously attempted, at least partly for political reasons."

"The aid received from the United States at any one time was comparatively modest, often consisting of obsolescent equipment that the United States Army no longer wanted. Outright gifts of material were sometimes accompanied by an agreement that further amounts were to be purchased commercially. The severe limit to American generosity, combined with the perennial backwardness and shortage of materiel in the Spanish armed forces, led to a certain amount of resentment among the military over the terms of the relationship with the United States.

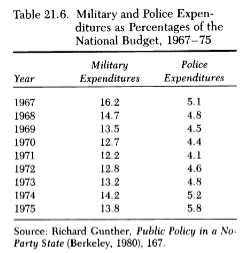

Certainly a regime primarily devoted to economic development and exhibiting a largely passive foreign policy felt no need to spend much money on its armed forces. Not only did the Spanish government maintain a relatively small military establishment compared with other European countries (table 21.5), but it steadily reduced the military share of the state budget (table 21.6). By 1973 Spain was devoting only 1.5 percent of its GNP to defense, a lower proportion than that of any other west European country save Luxemburg, and after 1970 for the first time in Spanish history, Spain spent more on education than on the armed forces.

The senior military command enjoyed great recognition and prestige, but opinion polls among Spanish youth in the 1960s indicated that a low- paid military career attracted little interest and that in the new urban, industrialized Spain a military career was not generally viewed as a prestigious one. Between 1964 and 1970 the number of new cadets in Franco's old Academia General Militar at Zaragoza dropped by two-thirds. The officer corps was increasingly isolated from the new urban society and had become largely self-recruited. During the years 1964 to 1968 in the Army academy, 79.6 percent of officer candidates were sons of officers or other military personnel, and the corresponding figures for the Navy were 65.8 and for the more modernistic Air Force 56.2.4” Moreover, salaries remained so low that 65 percent of the officers held part-time jobs to make ends meet.* It should be kept in mind, though, that this situation was to some extent characteristic of Spanish society in general, for most elite groups were to a significant degree self-recruited within their own cadres and pluri-empleo was a common middle-class phenomenon."

"If the military never wavered in support of the regime, what they thought of the current government was sometimes another story. In 1968 Carrero Blanco set up a new intelligence unit, which in March 1972 became the Servicio Central de Documentación de la Presidencia del Cobierno (SECED), under his own branch of government. It was to gather systematic information about political attitudes and activities, including possible subversion, in key sectors of Spanish society and institutions, including the military.”

Army “ultras” resented the influence of the civilian technocrats in the regime, who had introduced reforms and were dedicated to an uncertain monarchist succession, neither of which were pleasing to some of the old hard-liners...The vast majority of generals and officers, however, felt little desire for the officer corps to have to take responsibility for government again, and hence their reluctance to contravene its normal processes, whether under an aged Caudillo or a young king."

Foreign Relations

"López Bravos principal achievement in foreign affairs lay in negotiations with the European Community, with whom Spain entered into associate status through a treaty in June 1970 that provided preferential terms of trade. This arrangement opened the Common Market partway to Spanish exports without disturbing too greatly the Spanish protective tariff. Though full membership in the Community lay far in the future (and would not be arranged until a decade after Francos death), the agreement of 1970 offered Spain much of the best of both worlds, providing a new outlet for Spanish goods without subjecting the domestic economy to greatly increased competition.

Beyond this, López Bravos effort to carry on a more active foreign policy involved more travel and publicity than substance and achievement. Though Carrero and other hardliners prevented full resumption of relations with the Soviet Union, a commercial agreement was signed, a TASS office was opened in Madrid, and an EFE (Spanish news service) office was opened in Moscow. Regular diplomatic relations were established with East Germany and China, as well as consular agreements with Hungary, Poland, Bulgaria, Romania, and Czechoslovakia. López Bravo alsopaid special attention to relations with other Mediterranean countries and with Latin America. He made three trips to Latin America in 1971, visiting every country in the region except Mexico.” This accelerated activity could not change the fact that Spain would never enjoy fully nor- mal relations with its west European neighbors as long as the regime remained in power."

Politics During the Monocolor Government

"In general, Franco preferred that Juan Carlos make as few political statements as possible, both to avoid complications for the current regime and to allow him a freer hand of his own in the future. There was rarely cause for concern, since the Prince was known for his discretion, yet he occasionally felt the need to reach out to broader opinion. Thus early in 1970 he told Richard Eder of the New York Times that in the future, Spain would need a different kind of government than at the time of the Civil War and that as king he would become the heir of all Spain. This was published on February 4, 1970, under the headline “Juan Carlos Promises a Democratic Regime,’ with Eder further noting that those who talked with the Prince now found him better informed and more mature and determined than he had been, though still unsure how to proceed in certain respects.

Since the regime had for a quarter-century relied on official doubletalk about the “profoundly democratic,” “organically democratic” nature of the current system, Franco could not take great umbrage at verbal gestures made to American correspondents. He was nonetheless reported to be greatly annoyed by subsequent remarks made by Juan Carlos a year later on his official visit to the American capital, as reported by the Washington Post. The Prince therefore called on Franco immediately after his return to Madrid to gauge his reaction personally, but the Generalissimo merely observed sardonically, “There are things that you can and ought to say outside Spain and things that you ought not to say inside Spain. It may not be appropriate to repeat here what is said outside. And, at times, it might be better if what is said here is not picked up outside.”"

"Personal relations between Caudillo and Prince did not follow an altogether easy rhythm, for sometimes long periods would pass without a meeting, on occasion punctuated by a peremptory summons from Franco. Juan Carlos urged Franco during several conversations in 1970 to appoint a prime minister so that it would not be up to him to name the first president of government to follow Franco, but he was always answered vaguely that this would be done in good time. "

"Though the new government had pledged publicly to continue the “development” and “evolution” of the system, its apparent monocolor tone was deceptive, and the cabinet soon divided to some extent between hardliners and advocates of greater apertura, with the former gaining the upper hand. One of the first victims was the proposed new Ley de Bases del Régimen Local being prepared by the Ministry of the Interior. The law proposed that mayors be elected by local municipal councils, and would have permitted two or more provincial governments to form “Man- comunidades” for specific limited goals. "

"Carrero Blanco still sought to encourage further “evolution,” and in January 1971 handed Franco a detailed memorandum urging him to name a president of government in order to preserve his own strength and energy and maintain undiminished the prestige of chief of state. Carrero outlined a ten-point program for the first prime minister other than Franco himself to hold the presidency of government, but these had to do mostly with technical reforms and the reinforcement of authority. The only proposal involving political development was the suggestion for some sort of scheme of political associations.* Though Franco made no positive response to this, he did agree to a proposal by Carrero and López Rodó to clarify the terms of succession, publishing a decree on July 15, 1971, that conferred upon Juan Carlos the powers that properly pertained to the officially declared heir to the throne as stipulated in article 11 of the Organic Law. These included the right to take over the interim functions of chief of state whenever Franco might be physically incapacitated or out of the country. Meanwhile a special effort was made by Carrero Blanco and Fernando Liñán, the director general de política interior, to elect a number of new procuradores to the Cortes who were supporters of the succession of Juan Carlos. This objective was generally accomplished so that the final Cortes of the regime, which convened in November 1971, contained proportionately fewer old-guard Movement loyalists or die-hard members of the Bunker” than its predecessor.”"

"A protest culture continued to spread in the universities and among the intelligentsia, and the autumn of 1971 saw the first firebombings of left-leaning bookstores by ultrarightist squads (often in- directly subsidized by the government) to protest the expansion of leftist propaganda in Spain. This had little effect, for there were no new restrictions in the press laws, and with each passing year the de facto limited freedom of the press was used more widely, creating an alternative “parliament of paper” to the controlled assembly of the Cortes. In Catalonia an only partially clandestine Asamblea de Catalunya was formed, representing nearly all the leftist and liberal democratic opposition shadow par- ties and grouplets that had begun to spring up in that region. Nonetheless all this led only slowly to any significant mobilization. Most young people did not want to become involved, and nearly all those who did were careful to abide by the restrained rules of shadow opposition politics that had begun to evolve in those years. The consumer society and the new television culture were by that time in full development, and the great majority of Spanish youth were relatively apathetic about politics.” Thus there was no attempt to revert to the tight police crackdowns of earlier years, and the regime merely responded with its customary swagger and bombast."

"Hope that the current cabinet would take the lead in further apertura had meanwhile faded. It was sorely divided on policy and received no leadership whatever from Franco, who seemed content with immobilism. Moderate opinion therefore looked more and more to Juan Carlos as the only hope for a breakthrough, and a new political tendency, juancarlismo, emerged as the focus of those who sought new personal opportunities as well as peaceful reform in the future. "

"Whatever coordination the government enjoyed was mostly provided by Carrero Blanco, who on July 18, 1972, obtained from Franco the promulgation of two laws, one establishing the unified authority of the king over the government at the time of succession and the other providing that the vice-president would automatically assume the powers of president of government (prime minister) should the position of chief of state temporarily fall vacant at a time when no other president of government was about to be named. These regulations were designed to guarantee a smooth transition should Franco suddenly die without having named a president of government, avoiding the danger that elements of the Bunker would temporarily gain control and thwart the succession."

"Political publications and news reporting became increasingly daring and outspoken, representing a wide range of tendencies and opinions anserving as a surrogate for a political life that could have no formal existence. The weekly news magazine Cambio 16 soon established itself as the leading national news reporter and the most widely circulating advocate of democratic change, as its title implied. The Marxist economist Ramon Tamames, who earlier had written the most widely read general study of Spains economic structure, in 1973 published a new history of the Republic, Civil War, and Franco era as the final volume in a new multi- volume paperback history of Spain directed toward the mass university audience. Intellectually undigested neo-Marxism and French gauchisme were all the rage, as the latest radical theories from Paris and Milan were uncritically reprinted in Spain.

The scope of ETA violence broadened, bringing a spiral of assassinations, kidnappings, and bank hold-ups. In 1973 it was flanked by a small new Marxist-Leninist terrorist organization, known by the acronym FRAP, centered in the capital.* On May Day, as police were breaking up a leftist demonstration in Madrid, a young policeman was attacked by FRAP militants in an alley and literally hacked to death. The government attempted selective new police crackdowns and tightened up certain aspects of the Law of Public Order, but it was no longer in a position to command the full authority or apply the ruthlessness of former times. Moreover, the Spanish judiciary was also increasingly influenced by the growing liberalization of society and institutions and tended to be more solicitous of the civil rights of citizens than in earlier years."

"The growth of political violence tended to paralyze whatever initiative existed within the government for further reform. Though Carrero Blanco seemed to support some sort of associationism in his speech before the National Council on March 1, 1973, subsequent developments led him to draw back. The subsecretary of the interior had resigned the preceding month in protest against continuing government division and im- mobilism, ventilating part of his disgust in the press.*

As Carr and Fusi put it,

Something deeper than a mere ministerial malaise was afflicting the Francoist state: a crisis of the regime which had begun with the debates over political associations in 1967-69, a crisis of contradictions. Spain was officially a Catholic state, yet the Church was at odds with the regime. Strikes were illegal but there were hundreds of them every year. Spain was an anti-liberal state yet desperately searching for some form of democratic legitimacy. . . . “In Spain,’ the ultra right-winger Blas Piñar said in October 1972, ‘we are suffering from a crisis of identity of our own state.’"

"Franco finally accepted the fact that he was no longer in condition to run the government himself, and for the first time placed in operation the mechanism to appoint a new president of government. This required the Council of the Realm to present a list of three names from which the chief of state would choose. Franco apparently indicated that he wished to have Carrero Blanco on the list, to which the council added Fraga Iribarne and the old guard Falangist Fernández Cuesta. On June 8 the Caudillo ofhcially appointed Carrero Blanco, the first time in the history of the regime that anyone other than Franco held the position of prime minister.

The new cabinet was almost exclusively Carreros election, its common denominators being loyalty to the regime combined with reasonable technical competence and an at least moderate support of further aperturismo. "

"Formation of the Carrero Blanco government was seen by most of the now very extensive opposition as little more than an expression of im- mobilism, designed to provide for the continuation of Francoism after Franco. It actually represented a degree of change and timidly proposed to consider new reforms. This was not so much a monocolor government as a practical administration of reliable but flexible moderates. "

The Assassination of Carrero Blanco

"It was directed not merely against the existing government but against the future of the regime, so as, in the words of the assassins, “to break the rhythm of evolution of the Spanish state, forcing it into an abrupt leap to the right.* "

"They devoted ten days to digging a tunnel with a jackhammer that burrowed under the center of the street directly beneath which his car passed. Such an operation naturally created considerable noise and debris, but the etarra squad passed themselves off as sculptors creating large new art works with mechanical techniques. The manager of the apartment building was himself a part-time police employee but found nothing amiss in their peculiar activities, all of which was a further demonstration of the lessened police control during the later years of the regime. Electrical wiring enabled them to set off an enormous blast precisely underneath Carreros vehicle as it drove slowly down the street on the morning of the twentieth, creating a huge hole in the pavement and lifting the president's car high into the air, finally depositing it right side up on top of the fourth-floor roof of the church and Jesuit monastery across the street, driver, police escort, and passenger still in one piece but all quite dead.*

This created the most serious governmental crisis in the history of the regime. The date of December 20 had been chosen by the assassins be- cause the trial of the main group of leaders of the primarily Communist Workers” Commissions was to begin that day, and as many as a hundred illegal demonstrations were scheduled to erupt in towns all over Spain. As news of the magnicide spread, it was accompanied by a general sense of foreboding. All but three of the demonstrations were abruptly canceled, and the leadership of the clandestine Communist Party, largest and most active of the opposition groups, quickly moved to dissociate itself from the assassination. In Madrid some shops closed early and street traffic fell off as many citizens remained in their homes. The only confusion resulted from an intemperate order by the new head of the Civil Guard, Lt. Gen. Iniesta Cano, directing provincial commanders to open fire, if necessary, to control any disorder. The acting president of government, Fernández Miranda, moved quickly to cancel the order and was supported by the interior minister Arias Navarro and the navy minister Pita da Veiga (who according to regulations took over the functions of the minister of the army in the absence of the latter).” Military units were placed on alert, but there were no disorders whatever, though the assassins escaped into Portugal and from there back to France.*"